::cck::481::/cck::

::introtext::

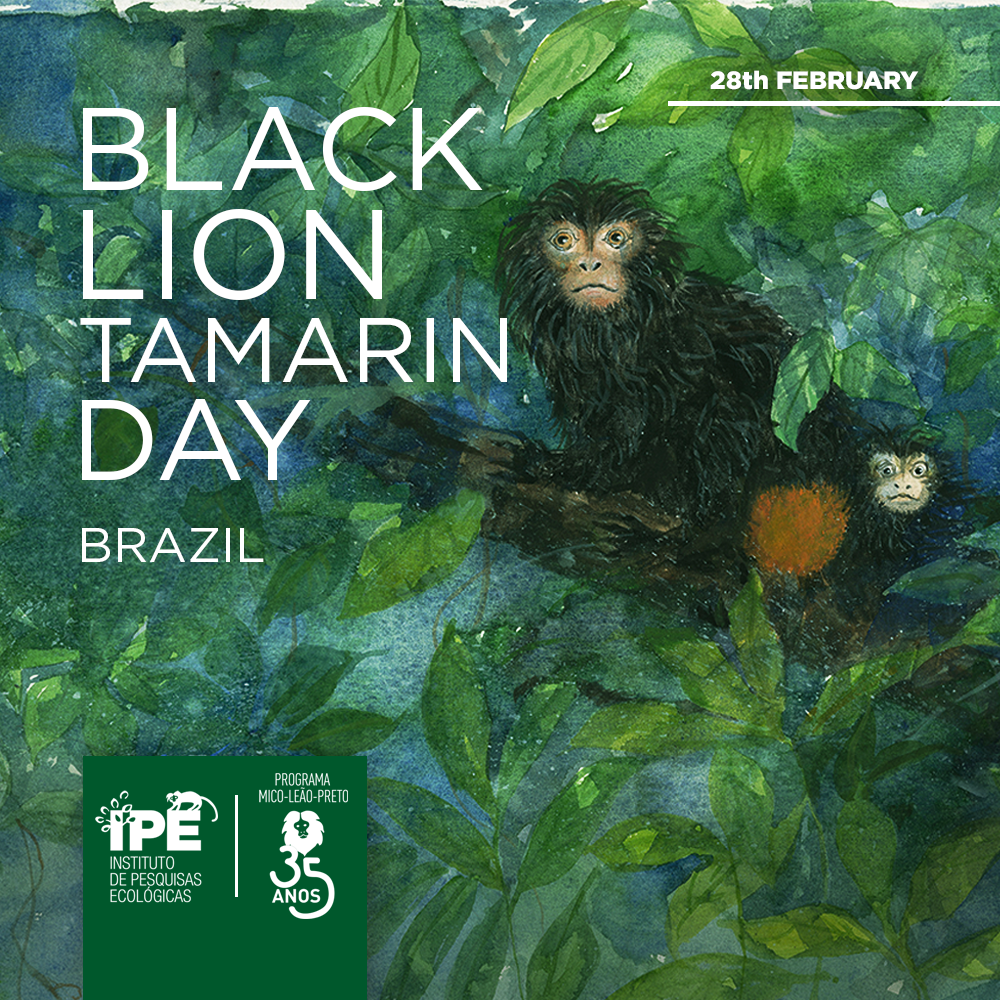

The Black Lion Tamarin Day will be celebrated in Brazil on February 28, for the first time. This small primate, whose scientific name is Leontopithecus chyrsopygus, is classified as “Endangered” in the international and Brazilian Red Lists of threatened species. Currently, it occurs only in Atlantic forest fragments in the western and southern portion of the Brazilian state of São Paulo, where it has an important ecological role.

Due to intense deforestation and fragmentation of its habitat, the population of the species has been reduced to about 1500 individuals. In fact, the black lion tamarin is so rare that it was not recorded for 65 years until its rediscovery in 1970. Fortunately, thanks to the conservation efforts of the socio-environmental and government agencies, today the black lion tamarin has a more promising future.

Like other primates, black lion tamarins act as sentinels (for example, their mortalities caused by yellow fever warn human populations of the presence of the virus), and they are also good seed dispersers, helping in the maintenance and regeneration of the forests where they live.

Because of these qualities and also due to the fact that it is restricted to a small area in the state of São Paulo, the black lion tamarin was designated the official mammal of the state in 2014.

Research for the conservation of the Black Lion Tamarin

IPE (Institute for Ecological Research) celebrates, in 2019, 35 years of service for the conservation of the black lion tamarin. The efforts have been concentrated in the Pontal do Paranapanema region, the westernmost tip of São Paulo state, and are carried out by members of the Black Lion Tamarin Conservation Program. In this region, field research on the behavior and health of the species are complemented by activities involving the community, environmental education and forest restoration, which guarantee the long-term survival of the species. IPE is responsible for obtaining scientific data that are used in public policies for the protection of this small monkey, such as the information used to create the Black Lion Tamarin Ecological Station, a federally protected area managed by the Brazilian government.

Another action important for the conservation of the black lion tamarin was the establishment of the largest reforested corridor of Brazil. As the Atlantic Forest in western São Paulo is extremely fragmented, the forest-dependent animals struggle to survive in small patches of suitable habitat, and virtually every subpopulation faces local extinction risk. One of the efforts led by IPE was to plant a native forest corridor that connects two large forested areas in Pontal do Paranapanema: the Black Lion Tamarin Ecological Station and the Morro do Diabo State Park. With 2.7 million trees, the corridor is approximately 20 kilometers long and helps the native animals to find shelter, food and reproductive partners.

The Atlantic Forest corridor, as it is called, is already sheltering several species of animals, including large mammals such as tapirs and jaguars, as attested by studies using camera traps. Use of the corridors by the black lion tamarins is being studied, but as the species uses hollows in old large trees as sleeping sites, which are not present in the young planted corridor yet, researchers from IPE are testing, in some areas adjacent to the corridors, if the tamarins would sleep inside artificial shelters. Monitoring of these artificial shelters is yielding promising results, as two groups of tamarins have been observed using the shelters. These results suggest that implementing artificial nest boxes in the planted corridors will ease the establishment of black lion tamarin populations there.

To celebrate the black lion tamarin day, IPE will promote several activities involving the local populace of Pontal do Paranapanema and also partners such as the Morro do Diabo State Park staff. The complete schedule will be available in the social media of @institutoipe.

Curiosities

There are four species of lion tamarins and they are only found in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil. The Golden Lion Tamarin (more popular, from the forest of Rio de Janeiro), the Golden-headed Lion Tamarin (from the state of Bahia), the Black-faced Lion Tamarin (occurring in a very small area in the states of São Paulo and Paraná), and the Black Lion Tamarin (from the interior Atlantic Forest of São Paulo state, especially in the western area).

Adult black lion tamarins weigh about 600 grams. Their body is covered by a long fur, predominantly black, except for the rump, which has an orangish color. They are called “lion tamarins” because of the little mane around the face.

They live in family groups containing from 2 to 8 individuals. Each group is composed of a dominant female, one or two reproductive males and the juvenile offspring, which remain in the group until they reach sexual maturity and disperse to form their own family groups. The female normally gives birth to twins once a year after a gestation period of approximately 4 months. The other members of the group help in raising the babies, until the juvenile can move by itself. Communication between the members is frequent and made through high-pitched whistles and chirps.

As they are territorial animals, each group uses an area, which can vary in size between 40 to 400 hectares. They are diurnal animals and during the night they sleep in tree hollows. When researchers study the behavior of the lion tamarins, they must locate the hollows used by the tamarins the day before so they can follow the group early on the next day.

Most of the diet of the black lion tamarin is composed chiefly of fruits, but they also eat tree sap, flowers, invertebrates and small vertebrates, such as frogs and nestlings. The main predators are birds of prey, boas, tayras and small cats.

::/introtext::

::fulltext::::/fulltext::

::cck::481::/cck::