Scientific article published in an international journal revealed that among primates threatened with extinction worldwide, only the black lion tamarin had its status improved

Photo credit: Lucas Leoni

Thirty kilometers separate the estimated main population of 1,200 black lion tamarins (Leontopithecus chrysopygus) in the Morro do Diabo State Park in the West of São Paulo from the new home for five of them, a forest fragment in a Legal Reserve area, also in the Pontal do Paranapanema region. The goal? To increase the chances that the local population of the forest fragment, which has fewer than 20 individuals, will continue to exist in the medium and long term.

“We chose the fragment population as the target of our action because there is a serious risk of extinction in the next 10 to 20 years, due to its small size and low genetic variety. By supplementing this population with more tamarins, we can buy time to, through the restoration of forest corridors, achieve functional connectivity with other forest areas in the region, which could take 20 to 30 years. We have observed a decline in this population and we urgently need to prevent this local extinction”, reveals Gabriela Rezende, coordinator of the Black Lion Tamarin Conservation Program at IPÊ – Ecological Research Institute.

Researchers from the Black Lion Tamarin Conservation Program have been monitoring the group of five monkeys in the park since April 2023. In January of this year, the team captured and identified the monkeys with microchips and released them into the new area that same morning. “We chose to carry out the activity between December and February, the time of year with the greatest availability of fruit, to increase the chances of the monkeys adapting and surviving in the new area. We also chose a group with subadult individuals, as these are animals at the age of dispersal. These individuals will ensure an increase in the genetic variability of the population, through the formation of new groups with local animals,” explains Daniel Felippi, veterinarian with the Program, which will be celebrating its 40th anniversary in 2024.

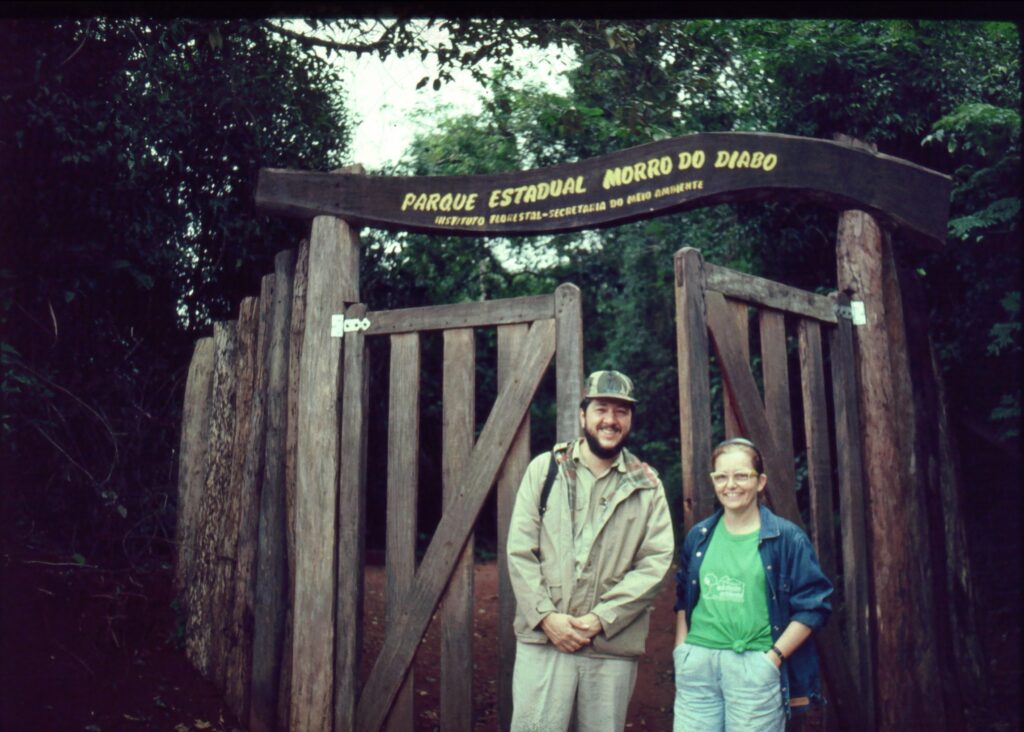

Legenda: Researchers Daniel Felippi and Gabriela Rezende during the translocation

Credit: Lucas Leoni

The removal of a group from one area and moving them to another is known as translocation. The initiative has also been closely monitored by professionals from ICMBio – Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation and the Forestry Foundation, which manages the Park, who have participated in all phases, from planning to issuing permits and updates. The action also has the approval of the Technical Advisory Group of the National Action Plan for the Conservation of Atlantic Forest Primates and the Maned Sloth. (PAN PPMA).

During the workshop for the development of the Population Management Program for the species in 2023, a monitoring group was established with those present and representatives. Gabriela Rezende also took on this coordination. The Program was published in the same year by ICMBio.

Program translocations moved a total of 27 black lion tamarins

The tamarins in a new location since January are participating in the sixth translocation performed by the Black Lion Tamarin Conservation Program. The first one took place in 1995 and four others followed until 2008. At the time, these management actions together moved 22 black lion tamarins to Fazenda Mosquito (Pontal do Paranapanema), a fragment where the species was no longer present. “Some tamarins were brought from Fazenda Rio Claro (Lençóis Paulista/SP) and others from fragments that were deforested in the Buri/SP region. IPÊ has been monitoring these monkeys at Mosquito since then so we know that this new population has managed to establish itself and remain in the area. We are planning to assess whether this population is already viable and self-sustaining or if we need more translocations to ensure its long term existence,” says Gabriela Rezende.

Data from monitoring this recent translocation in the Legal Reserve area at Pontal, Fazenda San Maria, show that two of the five monkeys remain together, one of them is the subadult female that carries the radio collar used for monitoring. “It is not possible to say whether the reduction in the group was due to death or emigration, both of which are plausible causes, considering that the group was composed of subadult individuals in the dispersion phase. Attempts to recapture the group to assess the health condition of the animals and identify which individuals are still part of the group are underway,” reveals the researcher.

Gabriela emphasizes that despite all the challenges, translocation is the most advantageous tool for populations at risk due to low gene flow. “The main actions that contributed to saving the black lion tamarin from extinction included population management, through the movement of lion tamarins from one fragment to another where the species was no longer found. This resulted in the establishment of a new population. Population management is a short-term strategy that should be worked on together with habitat management – its restoration”, adds the Program coordinator.

Legenda: Black lion tamarin climbs tree after release

Credit: Lucas Leoni

Fires

The fires that have been ravaging the country this year were also recorded in June in the Legal Reserve area where the monkeys were released. The area in question is monitored by satellite in real time by the Corridors for Life project, for the prevention and containment of forest fires (Pantera software, Umgrauemeio). “It was definitely a scare, but we know that the lion tamarins are fine. The heat source generated an immediate alert, which allowed us to activate the local brigades that are part of the Mutual Emergency Aid Plan (PAME). The joint and coordinated action of the PAME organizations ensured that the fire was quickly controlled, preventing the fire from spreading to the vegetation. As a result, only two hectares on the edge of the fragment were affected,” explains Gabriela Rezende.

Legenda: The area affected by the fire is close to the highway

Credit: Eriqui Marqueti

Next steps

Starting in September, the project team will conduct a new census in the fragment, using passive acoustic monitoring – done with autonomous recorders – and transects with playback that emits vocalizations. The goal is to update the population size and the patterns of use and occupation of space by the groups that live in the fragment. “Using technologies such as autonomous recorders and camera traps, it is possible to identify valuable information about the primates and the conditions of the environment in which they live, such as monitoring the size of the groups and the areas they are using in the fragment, or even determining the time of day when they are most active. We are moving in this direction, considered an emerging area for the conservation of different species of primates”, highlights the coordinator of the longest-running conservation program at IPÊ – Instituto de Pesquisas Ecológicas.

An innovation of the project since 2016 is the use of artificial hollows in forest fragments that do not yet have the supply of natural hollows or that have low availability of them. “Hollows are a valuable resource for the protection of black lion tamarins, especially at night, but they are not naturally available in recently restored forests. Our research shows that several arboreal species – which live in trees and do not usually step on the forest floor, such as opossums and some birds, in addition to tamarins – also depend on and use these artificial hollows when they are available”, highlights the researcher.

Legenda: Black lion tamarins use artificial hollows

The next steps include: consolidating the One Health program, integrating the health of tamarins with environmental and human health; in practice, evaluating how the disease cycle presents itself in tamarins, domestic animals and, especially, in communities living close to forest areas; advancing research using bioacoustics, through autonomous recorders, and on the impact of climate change on tamarins; in addition to developing various environmental education and communication actions. Population and habitat management actions integrate research results and complement community involvement strategies promoted by IPÊ, as a way of promoting the conservation of the black lion tamarin and the Atlantic Forest in its areas of occurrence.

Research with the lion tamarin created IPÊ

Research on the black lion tamarin began on the initiative of Claudio Valladares Padua in 1984. The business administrator left his profession in Rio de Janeiro to become a biologist and give his life a new purpose by working for nature conservation. The opportunity to do his part for biodiversity came through research on the tamarin in Pontal do Paranapanema. The research progressed with an environmental education component led by his wife Suzana Padua, and habitat restoration through several other projects. New researchers who joined the couple with an interest in research along these lines gave rise to IPÊ – Instituto de Pesquisas Ecológicas, in 1992.

Legenda: Claudio and Suzana Padua at the entrance to Morro do Diabo State Park in 1988

Since then, the initial research efforts into the ecology of the species have been expanded, explains Padua. “I started out wanting to save the black lion tamarin, but I realized that I wouldn’t be able to save it even if I studied everything possible about it. I discovered that it was necessary to include people, a work that was initially led by Suzana, but the economic side still had a lot of weight. We also began to work on the conservation of the tamarin’s habitat and the regional economy, working on landscape planning and influencing public policies. That’s how we created the IPÊ conservation model, which is based on science and community involvement.”

Both Claudio and Gabriela are internationally recognized for their work in conserving the species. Claudio received the Whitley Award from the Whitley Fund for Nature (United Kingdom), considered the Green Oscar of Conservation, in 1999 and Gabriela in 2020. In 2023, IPÊ received an additional category of the Whitley Award for the institution’s work.

Legenda: Suzana and Claudio Padua receive surprise award at Whitley Fund for Nature ceremony from Princess Anne

In March 2024, Gabriela also received a new award from the Disney Conservation Fund, one of the Program’s main funders, as one of 11 incredible women making a positive impact on conservation around the world, along with the amount of 50 thousand dollars invested in the Program.

Corridors for Life

Habitat restoration that started with this primate evolved to another IPÊ project, Corridors for Life, which brings the forest back by restoring strategic areas for connectivity between fragments. These areas include the connection between the two Conservation Units in the region, the Morro do Diabo State Park and the Black Lion Tamarin Ecological Station, established in 2002.

For Gabriela Rezende, it is essential that the Black Lion Tamarin Conservation Program move in two directions in parallel. “If we focus on management and do not take care of the habitat, we will not achieve the expected results. On the other hand, if we take care of the habitat without carrying out management, we may lose populations while the forest is being restored. The Corridors of Life project has already planted more than 6 million trees in the region, including 2.4 million that form the largest forest corridor ever restored in the biome. These are two demands that must be addressed simultaneously, since one contributes to conservation in the short term and the other in the long term.”

Legenda: The largest restored forest corridor in the Atlantic Forest with 2.4 million trees

Credit: Laurie Hedges

An article published in March 2024 in the journal Conservation Biology revealed that among primates threatened with extinction worldwide, only the black lion tamarin has seen its status improve in recent decades.

What has changed

After being considered extinct for over 60 years (1905 to 1969), the species was rediscovered in 1970 in the Pontal do Paranapanema region and was included in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species – International Union for Conservation of Nature – in 1982, as “Endangered”. At the time, there was a different understanding than the current one and the classifications of species were limited to “Extinct”, “Endangered”, “Vulnerable”, “Rare” or “Undetermined”.

In 1996, due to new IUCN criteria based on the extremely fragmented and reduced extent of its occurrence, the Black Lion Tamarin was classified as “Critically Endangered”. In 2000, it was included in the list of the 25 most threatened primate species in the world, drawn up by the IUCN Primate Specialist Group.

According to Gabriela Rezende, in 2008 the IUCN reassessed the status of the species, taking into account the entire body of work: ongoing field research, population management and habitat improvement due to the restoration project initiated in the Pontal do Paranapanema region.

Legenda: Credit: Gabriela Rezende

“New populations were discovered in the Upper Paranapanema, thus increasing the population size and the range of occurrence. In addition, we had the start of the IPÊ corridor restoration project, the creation of the Black Lion Tamarin Ecological Station (ICMBio), among other actions that made a difference in the IUCN assessment in 2008, which moved the black lion tamarin to “Endangered”, a more hopeful category”, explains Gabriela Rezende. The most recent estimate considers that 1,800 individuals live in the wild, distributed in approximately 20 locations in the state of São Paulo (between the Tietê River and the Paranapanema River), with approximately 65% of them in the Morro do Diabo State Park.